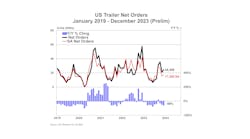

What goes up, must come down—and the trailer market has built steadily to the current record levels since the Great Recession. The questions for Don Ake, vice president, commercial vehicles at FTR, is when will the slowdown begin, and how far will production fall?

“How much momentum will we have from 2019 going into 2020?” Ake asks. “We’re expecting the freight growth rate to moderate throughout the year and going into the first part of 2020. And that should put the brakes on the record market we’re in right now. But we’re still expecting, even with that easing in the second half, for the trailer market to set another record.”

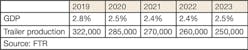

His forecast calls for 322,000 trailers to be built this year, topping the 317,200 that were built in 2018.

Next year, not so much. FTR forecasts slower growth in truckloadings, a demand driver, to come in at 2.1% for 2020.

“Freight growth is still good, but it’s not nearly as strong as it was in 2017 (3.4%.) and 2018 (3.8%), which ran up the need for more trailers,” Ake says. “So what follows is you have a record-setting year in 2018, and an expected breaking of that record in 2019. Back to back record years! That’s probably a first.”

Still, Ake puts 2020 production at 285,000 units, a decline of just under 12%—but that hinges on GDP growth of 2.5%, a rate, he concedes, that might be considered optimistic. In providing FTR’s 5-year trailer forecast to Trailer/Body BUILDERS, Ake is quick to note that his numbers don’t include a recession year.

“It’s pretty much impossible to forecast the recession with accurate timing,” he says. “But I am going to say that the risk is greater late in 2020.”

Additionally, because so many trailers have been built in the last two years, any “stumble” in the economy would mean an excess of trailers in the market.

Indeed, the slow but steady economic growth since the recession has been the key factor, but the trucking-specific dynamics that led to the recent capacity crunch have amplified the demand for trailers, as carriers reorganized operations around a drop-and-hook strategy.

“That’s been a challenge for the industry in the past,” Ake says. “When you have excess trailers out there, it can cause the cycle to go lower than it needs to be.”

The good news, however, is that the supply chain has become accustomed to operating with a trailer surplus, Ake suggests. To support his theory, Ake points to 2016 when the truck and vocational trailer markets slipped, but dry van and refrigerated trailers did not.

“Freight moves faster. Customer service is better. The freight industry, in general, likes this new system,” Ake says.

And he’s quick to point out that 285,000 trailers in 2020 is still “a great number.”

“So if you have a downturn, fine, you have excess trailers. It’s not like they’re going to sit forever. But, again, this is uncharted territory,” Ake says. “I’m almost hoping that I’m wrong [about a minimal downturn] and that it will be a normal, predictable cycle. That’s what people expect.”

Economic uncertainty

Recession or no, a breather is overdue.

“Because the freight growth is slowing, we expect the driver shortage to improve some, and capacity utilization comes down to more manageable levels for the fleets,” Ake says. “Right now, spot rates are not strong but, as things normalize, you would hope that they would stabilize. Maybe in 2020 the freight and equipment markets return to a more normal, manageable state—getting away from the chaos that we’ve experienced.”

The “wild card” in freight volume forecasts for the near future is the Trump administration’s trade policy, specifically the tariff plans.

“If the tariff impact disrupts the economy so much that GDP goes below 2%, then you’re going to have economic consequences and you will see the trailer build numbers drop lower than expected—maybe much lower than expected, depending on the environment at the time,” Ake says. “But that’s hard to quantify at this point.”

The impact of the tariffs on Chinese imports was minimal for freight, he suggests, because of a surge in shipments to beat the tariff deadlines. Those shipments clogged ports for a time, but the freight still moved. Shipments from Mexico would be more problematic, however.

“That introduces more uncertainty into the system, and that causes less investment,” Ake says. “It can cause fleets to pull back on purchases—but, again, it’s hard to quantify because we don’t even know what’s going to happen or how bad it’s going to be. But it’s out there.”

As for the impact the ongoing tariffs on steel and aluminum have had on trailer manufacturers, Ake suggests profits have been lower than would be expected in a boom cycle, and pricing—because of rising material costs in a time of record backlogs—has been a serious challenge. On the brighter side of the predicted 12% decline in trailer production next year, the pressure will ease on the supply chain as component suppliers should be more than able to meet that level of demand. Labor shortages, likewise, should ease with a softening economy.

“It’s been a tough a year and a half or two years on the supplier base, and their supplier base,” Ake says. “The tariff situation impacts them more than it does the OEMs because they’re sourcing parts from all over the world. They need predictable pricing and they need dependable delivery. And starting in 2018 they had neither.”

But he cited a recent FTR survey that found two-thirds of respondents felt the supplier base was doing better.

“If you give businesses enough time to adjust, they adjust,” Ake says. “However, you still have the one-third saying that [the supplier problem] is as bad or worse—and last year it was really bad. So you haven’t eliminated it all, but you’ve improved.”

Election year

Another wild card for economic forecasters is the impact the 2020 election cycle will have on business. Historically, Ake explains, the White House and Congress could be counted on not to anger voters with questionable policy choices.

“Both parties would even work together to boost the economy, because it was about getting reelected,” Ake says. “That was the old story, but right now things are so dysfunctional that I don’t see that happening.”

Yet the economy is still good. Ake also notes that it would usually be a year from the time equipment markets peak before any serious economic issues arise, and then another few months for those issues to show up in economic measurements.

On the other hand, business uncertainty could have a negative impact on investment during the run-up to a presidential election—especially if one candidate is perceived to be very pro-business and the other promises radical reforms. Ake points specifically to the immediate jump in business confidence following the election of Trump in 2016.

“If fleets are worried or concerned about the outcome of the election, they could pull back on orders and sales,” Ake says. “It’s going to be dependent on the sentiment and the expectations at the time.”

But those sorts of “what if” questions don’t quite fit in the models used to build a forecast.

“We’re all about our models here, and our numerical analysis, at FTR,” Ake says. “We don’t guess, we calculate. You can’t put that one into the calculator and have it spit out a result.”

Time will tell.

Ake and the rest of the FTR team will have their freight and equipment market models on full display in their annual Transportation Conference, billed as the “premier forecasting event of the year” and the only event that brings together all of the aspects of the freight transportation world into one place. That place is Indianapolis, Sept. 10-12. Go to ftrconference.com for details.