Crunching the numbers: FTR projects continued strength in truck, trailer markets

The foundation of the heavy-duty equipment market is, essentially, freight volume, FTR CEO Eric Starks emphasized to preface his forecast—and freight is strong. The question, following the big-picture economic outlook presented earlier in the annual conference: Just what do those broader indicators mean for freight demand and, in turn, equipment demand in the next few years?

“Because freight is such an important aspect to understanding equipment, we want to understand the manufacturing component,” Starks said.

Charting the ISM Manufacturing index, Starks points out that recent manufacturing growth is running at a pace not seen since 2004—“and 2004 was a good time, it was crazy.”

On top of that, business activity—as measured by core capital goods orders—has shown “healthy improvement” since the lull in 2015-2016. In addition, business inventories have been falling over the same period, another positive sign for freight. (Starks does note, however, that e-commerce demands as well as a tight transportation supply will keep inventory levels above what had been the ideal range established from 2005 to 2014.)

In tying those trends to trucking, Starks charted both the ATA Tonnage Index, which showed “substantial” growth since early 2017, and the FTR Loadings Index, which showed “healthy” growth. Critically, both measures are on the same upward trajectory.

“The current conditions on the ground continue to be very, very strong,” Starks said.

Similarly, a recent downward turn in the Trans4cast Weekly Spot Truck Market Demand Index should not be misinterpreted: That slip is from the record highs set earlier this year.

“Things are not back to normal,” he said. “We are still over double where we have been historically. So don’t be faked out right now.”

And as with last year, “hurricane season” can be expected to add additional transportation market pressure going into the fourth quarter.

Also a positive for trucking companies, rates “have been on a tear” since early 2017.

Don Ake, FTR vice president of commercial vehicles, then translated those trucking metrics into order activity, which he called “unbelievable.”

Specifically, North America Class 8 net orders closed out the second quarter at a record high, topping 50,000 units. Indeed, through August four of the top five order months have occurred this year. Those totals are also well above 2015, itself “a pretty great year,” and above the seven-year average.

“It’s a very dynamic time, a very interesting time,” Ake said.

Of note, Class 8 retail sales present “an issue,” running below 2015 levels, which Ake attributes to “a clog” in the supply chain. Initially, suppliers couldn’t keep up with OEM needs; but when the supplier problems eased, manufacturers couldn’t move the completed vehicles.

“Guess what? They can’t find drivers,” Ake said, noting the irony. “So our industry is actually restraining itself.”

The upshot is an anticipated spike in retail sales in the near future, “because we want fleets to get those trucks; we want dealers to get those trucks.”

As a result, backlogs have soared—but “hopefully, we’ve seen the worst,” Ake added. “It was severe, but it’s improved to just very bad.”

Of note, when comparing surging orders to Class 8 capacity utilization, the trends line up—meaning the orders are “justified” by market conditions, Starks pointed out.

Similarly, build totals compared to orders are also lining up, even as the lead time remains at record high levels.

Looking ahead, build slots have already been claimed for much of the first quarter next year, the second quarter is filling fast, and some OEMs are taking orders for the third quarter, Ake suggested.

“As these quarters fill up, at some point in the fall we’re just going to run out of booking capacity to fill and we may get a very low order,” Ake said. “That’s no reason to panic; if you average it out over 12 months it’s still probably going to be a record.”

The bottom line in FTR’s forecasting equipment sales is its “economically derived demand” calculation, the combination of the various economic and trucking industry inputs, Starks explained. That EDD measure can produce some significant swings, so FTR’s market projections are the product of smoothing the EDD’s ups and downs to “better replicate” what truckers have bought historically. The measure also provides insight into whether truckers are buying more or fewer trucks and trailers than the market would suggest.

“Right now, the data tells us that we are right back on track with what the economy is doing, and what the freight economy is doing,” Starks said.

And FTR expects the EDD and Class 8 retail sales basically to line up—and level off—through 2021. However, because the EDD model doesn’t account for economic risks, FTR’s projection has the sales total falling slightly below expected demand.

“But if everything is what we’re seeing, and our forecast of the economy and freight markets is correct, we’re still talking very, very high levels,” Starks said.

Additionally, the production constraints—specifically the fluctuating variable of supplier deliveries—“makes it very tough to nail down a number precisely,” Ake said.

Still, FTR has made its best guesses.

For quarterly Class 8 production through 2019, FTR projects 84,000 units and 83,000 units in this year’s remaining quarters, increasing to 87,000 units by the second quarter next year before slipping to 82,000 by Q4.

That brings the annual projections to a capacity-constrained 315,000 units for 2018; rising to 340,000 in 2019; coming down to 280,000 in 2020; 250,000 in 2021; and 245,000 in 2022.

“In order to get to 340,000, suppliers have to supply—and the supply chain is very tight,” Ake said. “Any variation or any problems in the supply chain from now through the end of next year is going to reduce the OEM’s ability to build and put that 340,000 in question. On the other hand, if suppliers can supply and builders can build, based on the EDD that 340,000 is probably too low.”

Indeed, current order rates would suggest production levels could be 360,000 or 370,000 for next year. Still, FTR calculated maximum theoretical capacity to be 375,000, according to Ake.

“But we know that doesn’t happen, because any problem, anywhere, from the first day of the year to the last, reduces that number,” Ake said. “We’re worried about suppliers and 340,000—so 360,00 is going to be even tougher.”

Starks also noted that OEMs would face a “tough call” to make the investments needed to ramp up production capacity “so late in the cycle.”

“We could get to 370,000-plus, but the reality is probably closer to 350,000, given how the industry has already responded,” Starks said.

In an alternative projection, under a mild-to-moderate recession the 2022 total would fall by 78,000 trucks to 167,000.

“There’s no such thing as a mild or moderate recession in the trucking industry,” Ake said. “Anything hurts.”

But Starks suggested a downturn will be manageable.

“Will this be a 2008-2010 event? No, it will not,” Starks said. “This is just to give you some numbers to have in your back pocket to start thinking about as we move forward.”

Trailer outlook

For the trailer forecast, supplier issues also are a variable in the analysis. Ake noted that suppliers began missing delivery dates in February, and lead times became “problematic.” Additionally, during the production surge in 2015, commercial trucks and trailers were one of the few thriving industrial segments. In 2018, transportation equipment OEMs are competing for finite labor and materials with many other sectors in a growing economy.

Among factors driving the trailer market upward, Ake pointed to slow but steady recovery from the Great Recession; to the increased use of drop-and-hook in dry vans, refrigerated vans and flatbeds; to an increase in types and varieties of refrigerated freight, requiring more trailers; and the Amazon effect, and the use of trailers as mobile warehouses as inventory is moved from brick-and-mortar backrooms.

Pointing to the recent record trailer orders for the month of July, Ake predicted the totals would continue to climb.

“If you had to bet, you’d say that we’re probably going to see a new record month in trailer orders in the next six months,” he said. “Unless the supply chain fails in the next three or four months, we’re looking real good.”

That will likely mean record backlogs, as well, he added.

And, as this issue of Trailer/Body Builders was going to press, FTR reported that—true to Ake’s wager—September trailers orders were a “tremendous” 56,000 units, exceeding the previous record from October 2014 by more than 10,000 trailers. September orders were 59% higher than August and up 133% compared to a year ago. Trailer orders for the past 12 months have exceeded 400,000 units.

Looking ahead to production totals following the second quarter’s record total of 81,881, FTR forecasts 79,250 trailers for the third quarter, and 75,024 trailers to close out the year. For 2019, the totals are projected to follow the same EDD curve as Class 8 trucks, rising to 79,700 in Q2 and slipping to 71,800 by Q4. And, as with Class 8, the economic model says these totals could be higher.

“In the second quarter next year things will start to slow down just a bit,” Ake said. “They won’t remain red hot, just hot. Then we’re predicting, finally, a general drop. It’s a drop—not a crash, consistent with a lower economic forecast.”

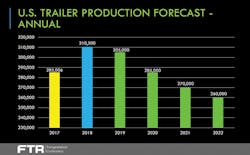

The annual totals are forecast to be 310,500 units for 2018; 305,000 in 2019; 285,000 in 2020; 270,000 in 2021; and 260,000 in 2022.

Among the segments, FTR predicts little change for 2019, with dry van and reefer off less than 2% compared to this year, liquid tank is down 3.2%, and flatbed slips 4%.

“We think the flatbed market will finally catch up with demand,” Ake said. “But a 4% drop, off of a high number, is not a bad number.”

Similarly, the next year’s gainers “have lagged” during the recovery, he noted.

Dump trailer production is forecast to be up 3.2%, dry tank up 2.3%, and low beds up 3.7%.

All in all, a strong forecast.

“Upside and downside? It’s all suppliers,” Ake said.

About the Author

Kevin Jones

Editor

Kevin has served as editor-in-chief of Trailer/Body Builders magazine since 2017—just the third editor in the magazine’s 60 years. He is also editorial director for Endeavor Business Media’s Commercial Vehicle group, which includes FleetOwner, Bulk Transporter, Refrigerated Transporter, American Trucker, and Fleet Maintenance magazines and websites.

Working from Beaufort, S.C., Kevin has covered trucking and manufacturing for nearly 20 years. His writing and commentary about the trucking industry and, previously, business and government, has been recognized with numerous state, regional, and national journalism awards.