Productivity is driving output, but jobs are representing a smaller share of total employment

MANUFACTURING output is in the process of recovering its losses, with its successes being driven by productivity, according to William Strauss, senior economist and economic advisor for the Federal Reserve Bank of Chicago.

“The most recent decline in manufacturing was cyclical, not structural,” he said. “Profits in manufacturing have outperformed profits for the rest of the nation. The trends that have dominated manufacturing for the past 70 years are suggestive of the future for US manufacturing: Ever-increasing output, with employment representing a smaller share of total employment.”

Manufacturing output peaked in December 2007, then fell 20.5% over the following 18 months. Manufacturing capacity utilization collapsed to the lowest rate (64%) in 70 years. Job declines in the manufacturing sector were “significant,” he said, with over 2.3 million jobs lost over that same period — one out of every four jobs lost during the Great Recession.

Manufacturing employment as a share of national employment has been declining for over 50 years. As a nation, we've gone from having one out of every three workers shortly after World War II engaged in manufacturing to just over 10%.

He said the number of jobs in manufacturing has been relatively stable over this period, edging lower on average by 0.3% per year since 1947.

“Manufacturing employment was increasing up until 1979 and has been moving lower over the past 30 years,” Strauss said. “Employment was rising by 0.8% — actually below the population growth of the period. Since roughly the mid-1970s, it has been falling by 1.5%. At the same time, service-sector employment has grown more than fourfold over this period, averaging growth of 2.3% per year since 1947.

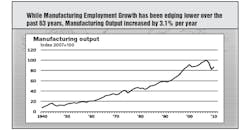

“In December 2007, the month before the recession began, manufacturing output was at record high. We were producing more than we ever have. Over this very long time period — 64 years — we were increasing at a good clip. The question is, how can you be increasing output and employment's been flat? The answer is productivity. While manufacturing employment growth has been edging lower over the past 63 years, manufacturing output increased by 3.1% per year. This translated into an almost 600% increase in manufacturing output over this time period.

“From my standpoint, these trends have been going on for 50, 60 years. Tell me why it's going to change. People talk about the fact we can do things differently, but when a series has been moving in this pattern for this many decades, it's hard to turn that shift around.”

He said that what took 1000 workers to produce in 1950 now takes 177 workers. If output had stayed the same as it was in 1950, we would have seen an 80% drop in employment.

“Who isn't in favor of productivity?” he said. “It means you can produce more with less. The problem is that when you talk about productivity, you're often talking about using less labor. That's what people get upset about. They love productivity but don't like the consequences.”

Sector growing faster

During the 1950s and 1960s, productivity for the non-farm business sector of the economy was identical to manufacturing. It wasn't until the 1970s that manufacturing production pulled away. By the 1990s, it was experiencing 4.1% growth, compared to 2.1% in non-farm business.

“As CNC applications came into play, it made things far more productive,” Strauss said. “In the more capital-intensive durable manufacturing, it has had an even more significant impact than in non-durable.

“Strong productivity growth had allowed the manufacturing sector to grow faster than the overall economy up through 2007. This sector is not disappearing. It's rising in line with GDP. However, lower relative prices in the manufacturing sector have lead to manufacturing comprising a smaller share of GDP over time. How could a sector that in essence has been rising faster than GDP become a smaller share of GDP? The answer to that conundrum is that we're right back to our good friend: productivity. Because of productivity, the value and prices you charge for goods you are making are rising at a slower rate — in some cases falling over time — than the rest of the economy's prices. When you look at the value of your goods compared to lawyer salaries and doctor salaries and other pieces of the economy, it's representing a smaller piece.”

Strauss said that one of the most frequent questions he gets at his speaking engagements is, how much more efficient can we become?

“I have yet to meet one manufacturer who even makes the suggestion that there still isn't a tremendous amount of improvement that can take place,” he said. “With regard to R&D expenditures, historically we have spent 2.5% to 3% of GDP on R&D. It's been picking up a bit.

“Over time, the vast majority of US research and development is being privately funded. If you think the market is a better place to make decisions on where to locate and decide what path to follow, this should be heartening to you. It says the private sector is probably going to get better bang for the buck on the efforts it puts out with regard to dollars spent.”

Declines in manufacturing output were broad-based during the Great Recession — especially in motor vehicles and parts (down 50% between December 2007 and June 2009), primary metals manufacturing (down 42%), and furniture and related products (36%).

“But like a tennis ball, the industries that fell the most are bouncing up the highest right now,” he said. “The recovery has also been broad-based, with motor vehicles (up 73%) and primary metals manufacturing (up 50%) leading the way. The fast-growing high-tech sector is averaging below machinery during this period (22%). I think it's very much related to this terrible labor market we've been dealing with. Tepid growth in employment has meant that you don't need to be buying electronics equipment — computers, Blackberrys, iPads — to outfit the workforce to be productive. Until the labor market comes back, I think the high-tech side is going to struggle.”

How do we produce more and more with fewer and fewer people?

“We have seen this type of operation before,” he said. “There's a reason why our statistics talk about ‘non-farm.’ That's because the farm sector is incredibly productive. The farm sector has continued to show output that rises ever-increasingly higher. I don't think anybody would suggest that agriculture is not an important part of our economic outlook. We produce enough to feed us and then other parts of world.

“Same story in manufacturing. We're continuing to have ever-increasing larger output without the need to use our resources, our people, to do that. What are we going to do with the people who are not in manufacturing? That's a whole other story. As I suggested to Congress, ‘You want to make manufacturing jobs go higher? Make us less productive.’”

Beginning in July 2009, manufacturing output in the United States has been increasing at a 5.5% annualized rate and has recovered 54.3% of its drop in output.

After reaching lows in manufacturing capacity utilization (64%) that hadn't been seen in 70 years, the US has rebounded impressively to 76% — still below the level of 80% that is regarded as full utilization.

He said 334,900 jobs have been added over the past two years.

“It's better than losses,” he said, “but a lot of this is that the pendulum went too far and now is swinging back. The 334,000 jobs added represent 14% of the jobs that were lost. We brought back 60% of output, but only brought back 14% of the workers. There are people who are thinking about this as the new ‘manufacturing renaissance,’ but I'm very suspect of that, especially when they focus on the labor side.”

Trade with China

China has risen to the top spot in US imports, representing 19.1% of all imports in 2010, followed closely by Canada and Mexico.

“While China has risen to be our third-largest export country, it represents only 7.2% of US exports,” he said. “China gets picked on quite a bit for this large differential. This difference has led to China having the largest trade deficit with the US.

“China has become the low-cost assembly point for Asia. A lot of what is assembled is components that are shipped into China, put together and then … For example, if somebody is going to build a Blu-ray DVD player, they can send all the high-value componentry produced from Japan. China is going to assemble it and box it up. But rather than sending it to Japan, who could then send it to us — that's not logistically smart — they put it on a container to us and it hits our shores and says, ‘$100 DVD player made in China.’

“China has certainly increased the amount of goods flowing into the US. They have also represented the largest gain for exports from the US. While China has increased its share of imports to the US, the Pacific Rim as a whole has had a declining share since the mid-'90s. There's a burgeoning trade deficit you can't blame on the Pacific Rim. It's happened from all over the world.”

About the Author

Rick Weber

Associate Editor

Rick Weber has been an associate editor for Trailer/Body Builders since February 2000. A national award-winning sportswriter, he covered the Miami Dolphins for the Fort Myers News-Press following service with publications in California and Australia. He is a graduate of Penn State University.