Whether it’s through environmental concerns, improvements in technology, operational benefits or all three, electrification is coming

John Bennett, vice president and chief technology officer at Meritor, doesn’t know how many medium- and heavy-duty trucks will be electric by 2025. Neither do industry pundits, whose predictions are widely varied.

But that’s OK, he says, because the exact number isn’t important anyway.

“What is important is that everybody is at least predicting that it’s higher than today,” Bennett said. “It is going up, absolutely. I haven’t heard anybody not believe that, so from that standpoint, it will impact our industry.”

That impact could be so great, it “revolutionizes” the industry, he maintained, and the effects of the trend toward more battery-electric vehicles in the commercial sector already are being felt in the bevy of acquisitions, consolidations, startups and investments as companies positions themselves for an electric future.

Bennett pointed to three main drivers of electric acceleration in commercial vehicles in his presentation “Not Your Dad’s Battery Technology” delivered during FTR’s 2019 Transportation Conference in Indianapolis IN, including environmental concerns, improvements in battery technology and expanding charging infrastructure.

The Sticks

“In the near term, the industry’s going to be forced to do some things,” Bennett said. “In the long term, I believe the industry will want to do some things, but it starts with the sticks (ie legislation that forces change).”

Whether people believe them or not, stories about climate change are in the news every day. The World Meteorological Organization, which tracks global temperatures, says 20 of the hottest years ever recorded have occurred in the last 22 years—and the last four years were the hottest. If the average temperature on Earth increased by 3 degrees F by 2050, enough ice will melt to raise ocean levels by 1 meter, devastating coastlines.

“I don’t know if I believe it but a lot of governments do,” Bennett said.

Carbon dioxide (CO2) production is a primary contributor to the buildup of greenhouse gasses affecting the climate, and the US, China and the European Union are responsible for half of the world’s CO2 production. In the US, 10 states, including Texas, California and Pennsylvania, account for half the country’s CO2.

Previously, the legislative response to environmental concerns focused on reducing emissions of nitrogen oxide (NOx) and particulate matter, but now, with an increasing emphasis on CO2 production, leaders are calling for CO2 reductions like the ones legislated by the European Union, which is calling for a 15% decrease in CO2 by 2025 and another 15% by 2030, or establishing “low-emission zones” as in London, England.

“This is the strategy that is starting to play out throughout Europe and in many Asian cities as well,” Bennett said. “There’s going to be this gradual increase of these low-emission zones, and you won’t be able to enter the zone without a battery-electric truck.”

The United Kingdom and France has legislation on the books committing them to net-zero CO2 production by 2050, and all the Nordic countries have similar plans. So what about the US? It depends on whether we’re talking federal or state. While the Trump administration is busy rolling back environmental legislation, and pulling out of the Paris Agreement, many states, led by California, are moving ahead with plans to generate all electricity by renewable means (solar, hydroelectric, etc) in the next 30 years.

The Carrots

On the end of those sticks are the carrots, or, in this case, the financial incentives for businesses to invest in battery-electric vehicles that still cost far more than a diesel truck. Bennett estimated the price of an electric terminal tractor is $150,000 more than its diesel counterpart, and an electric transit bus costs $200,000 more.

California, recognizing this, instituted the Hybrid and Zero-Emission Truck and Bus Voucher Incentive Program (HVIP), and other states have similar plans. With HVIP, depending on the size of the vehicle, the state will provide up to $315,000 for the purchase of a hydrogen fuel cell truck with a gross vehicle weight rating of more than 33,000 pounds.

Of course, incentives are only great until the dry up, but falling battery prices are another driver that promises to keep adoption moving forward. Based on Boston Consulting Group EV battery cost projections, batteries cost $1,200 per kilowatt hour (kWh) in 2009, so a 100-kWh battery pack, which supplies roughly enough energy to power a school bus, costs about $120,000.

The same pack today costs $25,000—and the price is expected to fall to $15,000 by 2025.

“Tesla’s talking about a 1,000 kWh—a megawatt hour—battery pack for a Class 8 truck with enough range to have any real long-haul value,” Bennett said.

As the price falls, so, too, are the size and weight of batteries—from 1,000 kilograms 10 years ago to 600 kg today and potentially only 400 kg within the next five years—protecting payload capacity and profit potential.

“Environmental reasons are great but the real benefit of an electric vehicle is that the operating costs are less when it comes to two places—electricity is less expensive than diesel … and the maintenance is less,” Bennett said. “There are far fewer parts on these things.”

The payback

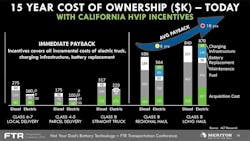

Bennett estimated an electric truck, vs a diesel truck, can save fleets $3,000 to $12,000 on energy expenses every year, depending on distance traveled and current diesel and electric prices; and up to $11,000 per year on maintenance costs, depending on miles driven, duty cycle, emissions and engine type. But those savings are only beneficial if fleets can realize them during the life of the vehicle—and the faster the better.

Without incentives, today, the payback is too long, Bennett said, ranging from seven to eight years in best-case scenarios—and 30-plus in the worst. “(But) for the medium duty and the Class 8 straight truck, with those same incentives in the HVIP program, the entire incremental cost is covered,” he said. “So you get immediate payback, and it brings the bigger long-haul vehicles down.”

Looking out to 2030, assuming battery costs continue to decrease and incentives eventually go away, Bennett’s predicting an eventual 1.6-year payback for battery-electric Class 6-7 local delivery trucks, three years for Class 4-5 parcel delivery vehicles—and immediate (zero-year) payback for Class 8 straight trucks.

“This is where it starts to make sense,” Bennett said.

“And instead of getting beaten into submission through regulation, it’s going to start making sense for your business.”

The pace of change depends on all the factors previously mentioned, like regulations and battery prices, along with many others, including diesel truck cost—which continues to increase as more and more emissions equipment is added to the purchase price—and the growth of charging infrastructure through investment.

But the exact date isn’t important. Electric disruption is happening, so don’t get caught off-guard.

“Electric trucks are absolutely coming, so take advantage of the incentives while they’re out there and try these vehicles in your operation, because every operation is different and you’ll have to find out how much savings you get on maintenance for yourself, how much energy consumption based on your routes, etc,” Bennett said.

About the Author

Jason McDaniel

Jason McDaniel, based in the Houston TX area, has nearly 20 years of experience as a journalist. He spent 15 writing and editing for daily newspapers, including the Houston Chronicle, and began covering the commercial vehicle industry in 2018. He was named editor of Bulk Transporter and Refrigerated Transporter magazines in July 2020.